What floats in the water, makes the river green, creates half our oxygen and without a microscope remains unseen?

It’s plankton!

Plankton are a group of mostly-microscopic, floating organisms with a worldwide impact. Each year around this time, we look forward to a special seasonal event that our waterways experience: the plankton bloom. This explosion in plankton population jumpstarts our local Hudson River aquatic ecosystem after a long, cold winter.

Plankton blooms are a great opportunity for us to observe the diversity of microscopic organisms that make their home in the Hudson River Estuary. With this year’s bloom underway in Park waters, let’s explore some of the different classifications of plankton and how they contribute to the ecology of the Park’s 400-acre Estuarine Sanctuary waters.

Plankton are a broad group, including lots of different types of organisms found in waterways around the world. To better organize this diverse set of organisms, plankton are divided into sub-groups that share similar traits. The most commonly referenced groupings are phytoplankton and zooplankton. Phytoplankton are plant-like single-celled, floating photosynthesizers that are usually identified by their green color and lack of complex anatomical features that are seen in zooplankton. Zooplankton, on the other hand, are animal-like plankton that can be identified by more rapid movements and complex body parts like eyes, limbs and tentacles.

We see varieties of both phytoplankton and zooplankton in our Estuarine Sanctuary. Read on to learn more about some of the most common members of our Hudson River plankton community.

Phytoplankton

Phytoplankton make up a significant portion of the base of marine food chains by producing huge amounts of sugar and oxygen that are used by other organisms higher in the food chain. In fact, phytoplankton produce so much oxygen that not all of it stays in the water — literally half of the oxygen you are breathing right now is produced by these organisms.

While we place all of these photosynthetic organisms under the name phytoplankton, this group is actually a collection of a number of different groups of organisms that survive and behave in very different ways. We’re going to feature two of our favorite groups of phytoplankton below: diatoms and dinoflagellates.

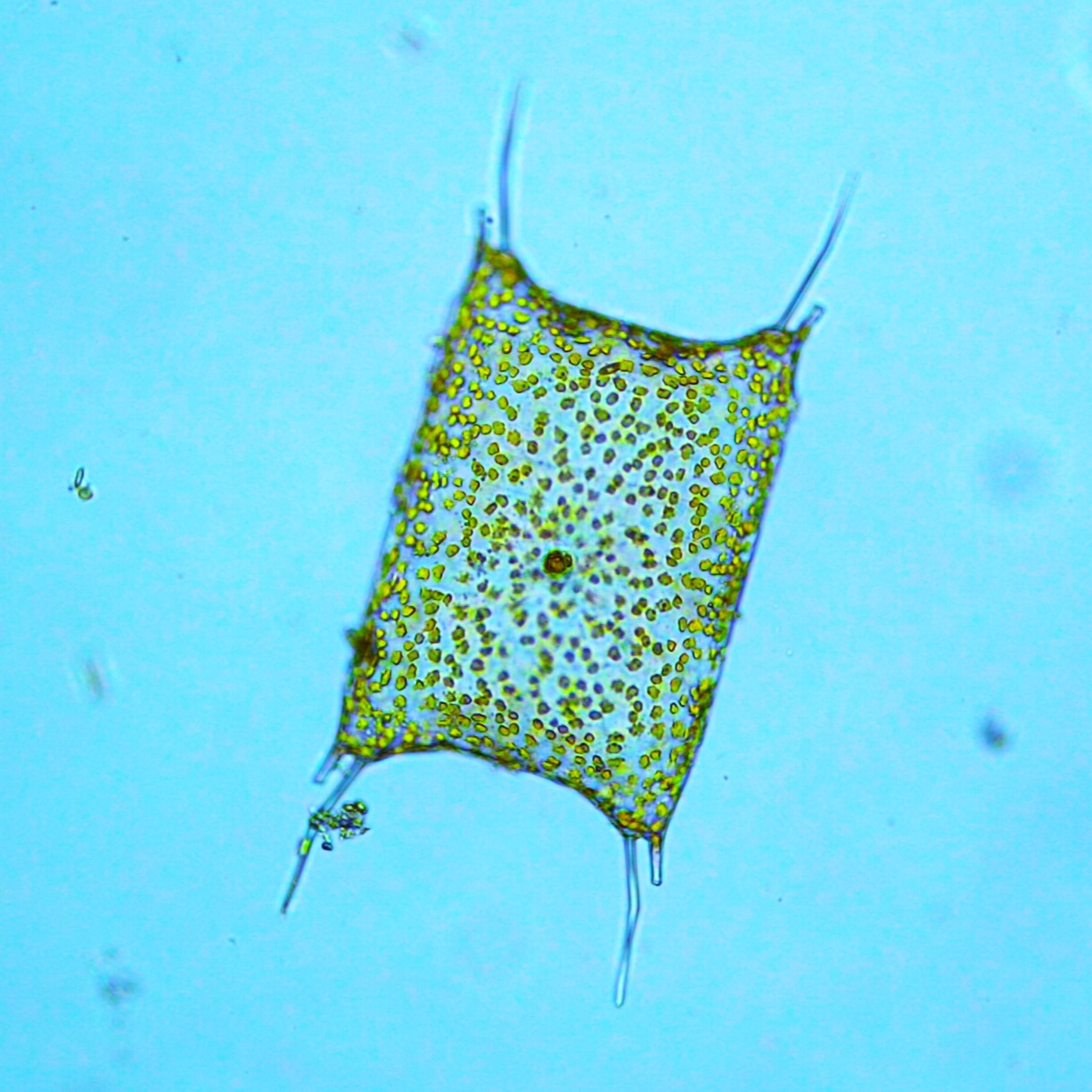

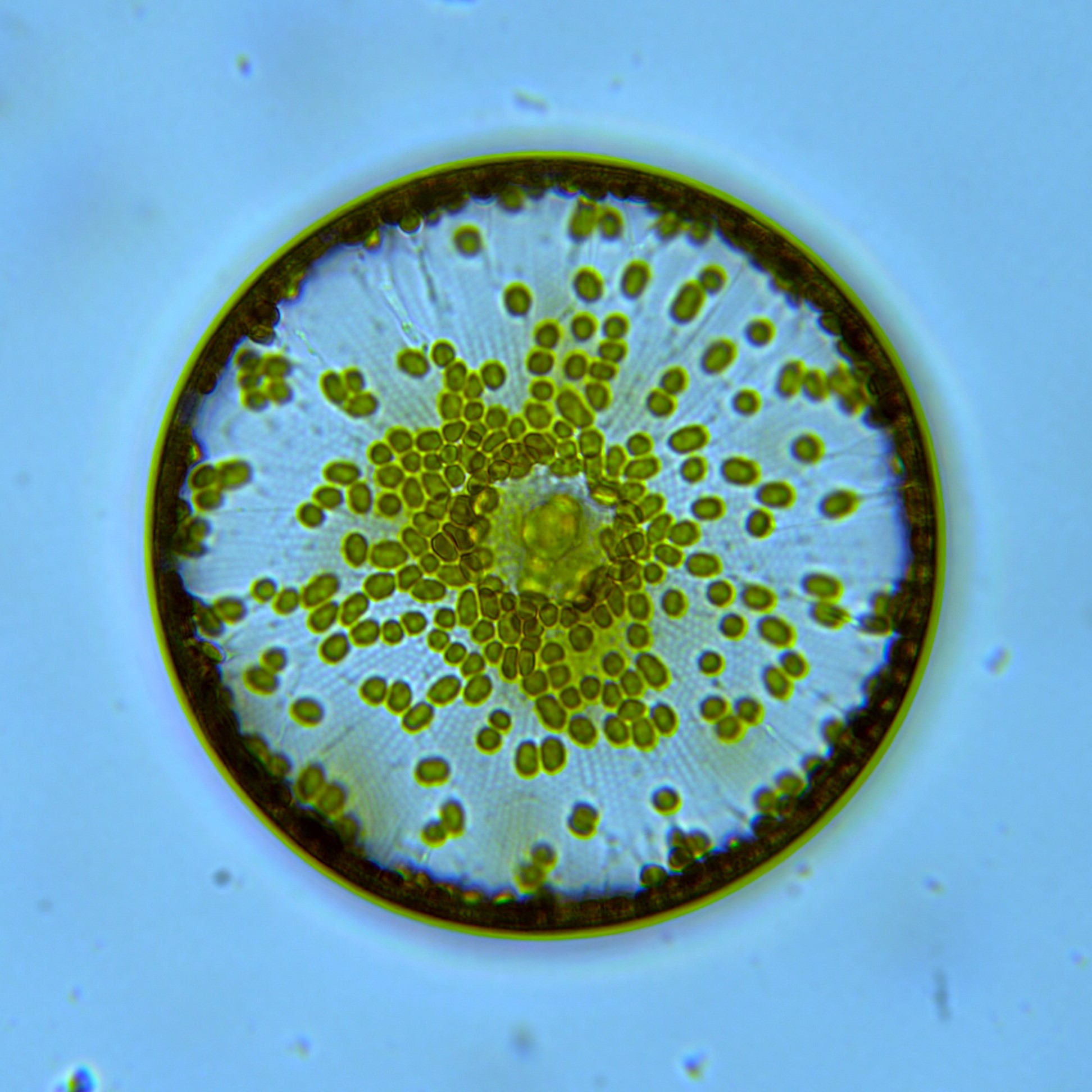

Diatoms

If plankton could throw stones, diatoms definitely shouldn’t because the defining feature of diatoms is a silica frustule, which is a glass shell encapsulating their body. This transparent casing protects the diatom while allowing light to pass through to be received by its chloroplasts, the part of their cell where photosynthesis takes place.

There are thousands of species of diatoms with variations in shape, pore arrangement and lifestyle that differentiate them from one another. They are the most abundant phytoplankton group, with intricate glass casings and a wide range of beautiful colors. The diatoms shown here, collected exclusively within Hudson River Park’s Estuarine Sanctuary, showcase only a small fraction of the diversity of this fascinatingly important group.

Dinoflagellates

Dinoflagellates are weird in a couple of ways. For starters, they are characterized by the presence of two flagella, which are whirling hairlike structures used to move up and down in the water column. While this ability to move may sound entirely un-plantlike, that is only the beginning of how this group defies our expectations of a photosynthetic organism.

Many dinoflagellate species are capable of both performing photosynthesis as well as feeding on other organisms, classifying them as mixotrophs. In their own way, they are a bit like microscopic venus fly traps — they will soak in the sun and do photosynthesis when light and nutrients are available, but many species will resort to eating other organisms when low light, low nutrients or other conditions limit their rate of growth and reproduction. Some dinoflagellates even act as tiny plant-vampires, sucking out chloroplasts from other phytoplankton to use in their own bodies.

Zooplankton

Plankton diversity takes off even further when we zoom into zooplankton. Commonly described as animal-like plankton, zooplankton are heterotrophic, meaning they need to consume other organisms in order to survive. This group includes floating animals like jellyfish and single-celled organisms like amoeba and ciliates. Nearly every phylum of organisms is represented in the zooplankton community — crustaceans, mollusks, worms, fish and more are part of this group. Though you might not think of many of those creatures as plankton, the defining feature which earns them this classification (at least for part of their life cycle) is their inability to swim against currents, meaning that they drift through our waterways, carried along by currents.

Zooplankton represent the second and third levels of marine food webs and play an important role in these ecosystems because they consume phytoplankton and other zooplankton before being consumed by organisms higher in the food chain. This transfers energy from lower in the food chain to higher levels where it is used by larger fish, invertebrates and marine mammals. If you eat fish, oysters or other marine organisms, you are also connected to these same food chains!

Holoplankton and Meroplankton

Zooplankton species belong to one of two groups — holoplankton and meroplankton. Holoplankton complete their entire life cycle as plankton. The most common holoplankton are copepods, which are small crustaceans that can be found in a wide variety of fresh and saltwater environments.

Meroplankton, on the other hand, only spend a portion of their life cycle as plankton. Some meroplankton mature into nekton, which are organisms that can swim against currents, while others mature into sessile, non-moving adult forms. Often, the adult forms of meroplankton are very recognizable River critters. For example, barnacle larvae begin life looking very similar in size and shape to copepods, but over time, they undergo a metamorphosis which includes building a shell and cementing themselves onto a surface where they will spend the remainder of their lives.

Bloom & Beyond!

This has only been a brief introduction to this complex group of organisms that have a significant effect on our planet. Often small in size, but mighty in impact, plankton have been used in medicine, nutrition and even as a potential source of sustainable fuel.

Analysis of plankton populations has become an important metric for predicting the health of the fish populations that rely on them. Paleobiologists even use fossilized plankton samples to analyze ancient climates, giving us a better sense of how our own climate is currently changing. And as our climate continues to change, it is important for us to keep track of how plankton react to shifting temperatures, salinity and other conditions that influence them. That is also why we track important annual trends, like the plankton bloom.

Want to learn more about plankton? Be sure to stop by our Pier 57 Discover Tank during Guided Gallery hours all month. From live samples to interactive games, you’ll have a chance to dive deep into this topic with our River Project team. Visit our events calendar for details and upcoming programs.