As we enter the final stretch of our Countdown to Spring, we’re beginning to see true signs of the season to come in Hudson River Park. If you have been following along with us, we have already explored how the original inhabitants of Manhattan, the Lenape, marked the passage of time through seasonal changes in the ecosystem and shared some of our favorite pieces of spring wisdom.

Believe it or not, one of the biggest changes that takes place in HRPK each spring happens below the surface of the Hudson River. As conditions become just right, drifting plants, animals and other organisms, collectively called plankton, begin to reproduce and multiply — rapidly!

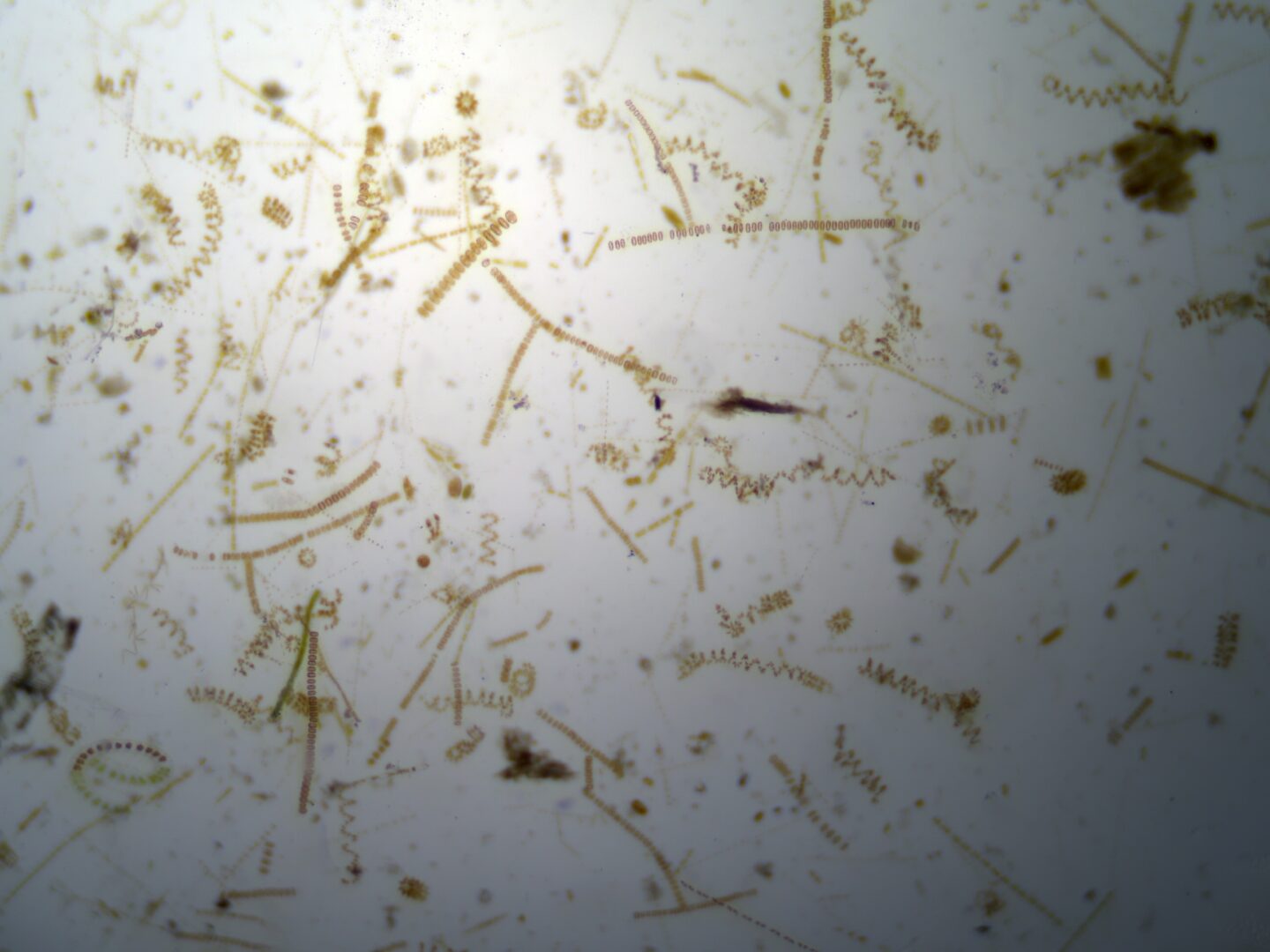

This phenomenon is called a plankton bloom, an important seasonal occurrence that offers an amazing showcase of the microscopic biodiversity of the Hudson River Estuary. Keep reading to learn more about how plankton blooms work and see some of the microscopic marvels that have been found in plankton samples this year!

This phenomenon is called a plankton bloom, an important seasonal occurrence that offers an amazing showcase of the microscopic biodiversity of the Hudson River Estuary. Keep reading to learn more about how plankton blooms work and see some of the microscopic marvels that have been found in plankton samples this year!

Plankton are small, often microscopic organisms that cannot swim against currents and instead drift and float in the water column. Plankton are broadly categorized into two categories: plant phytoplankton and animal zooplankton. Phytoplankton (also known as microalgae) are primary producers. Like plants on land, phytoplankton conduct photosynthesis: they use sunlight, carbon dioxide, nutrients and water to produce food and oxygen.

The term “bloom” usually makes one think of flowers or plants, but it’s also a great description for plankton, because plankton blooms start with phytoplankton. This annual phenomenon starts in late winter, when phytoplankton start to bloom for two main reasons. First, at this time of year, we start to get more sunlight, which warms the water and provides more energy for photosynthesis. Second, this change in water temperature leads to seasonal mixing, during which deep, nutrient rich water is brought to the surface, where phytoplankton can make use of the carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and other materials they need to successfully grow and reproduce.

Together these conditions result in a visible bloom, and you can actually see the presence of phytoplankton in the River by looking at the color of the water. The greenish hue that characterizes the Hudson River Estuary, which is especially visible this time of year, comes from the green pigment chlorophyll that phytoplankton use to capture sunlight, just like plants.

Together these conditions result in a visible bloom, and you can actually see the presence of phytoplankton in the River by looking at the color of the water. The greenish hue that characterizes the Hudson River Estuary, which is especially visible this time of year, comes from the green pigment chlorophyll that phytoplankton use to capture sunlight, just like plants.

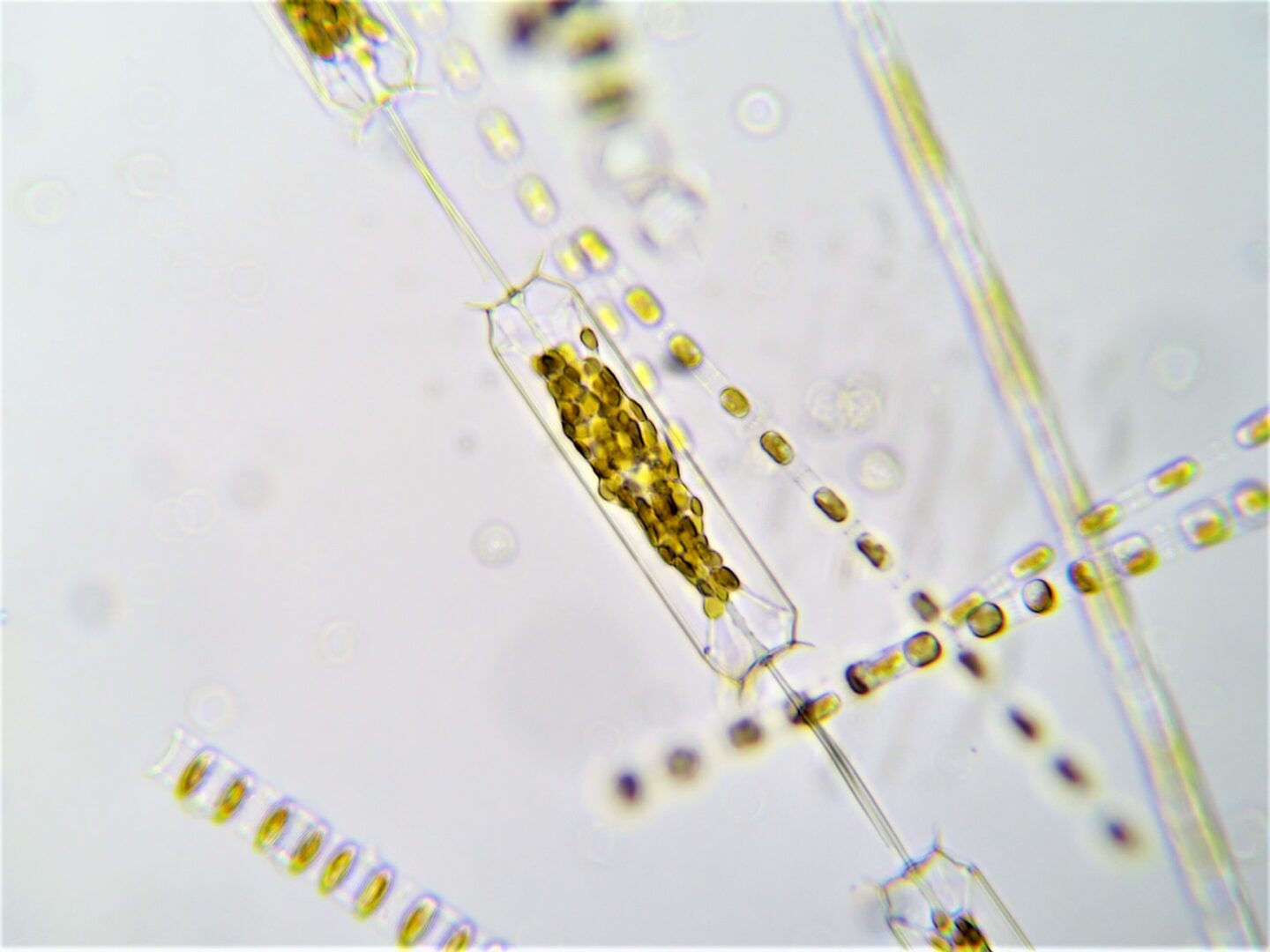

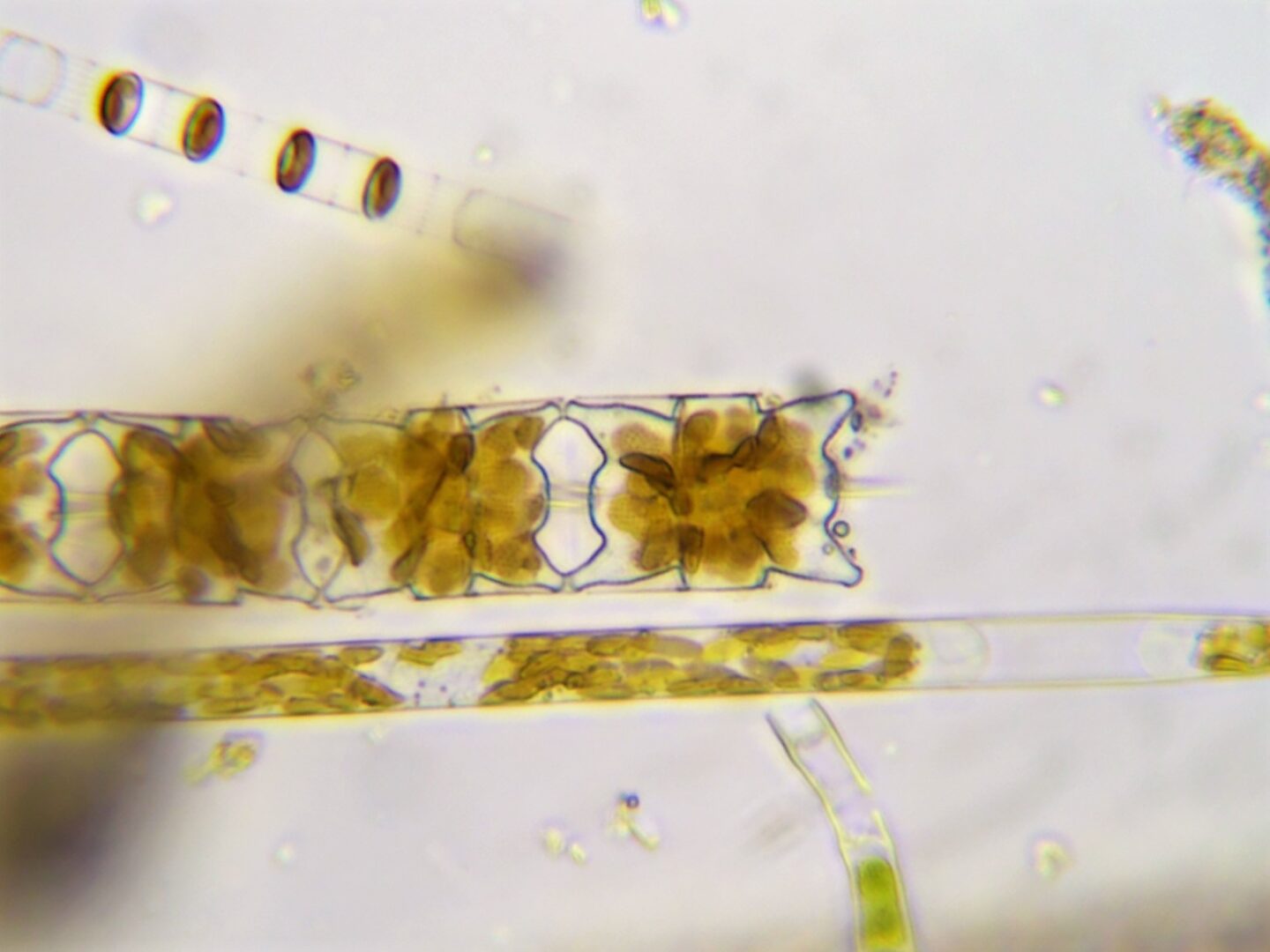

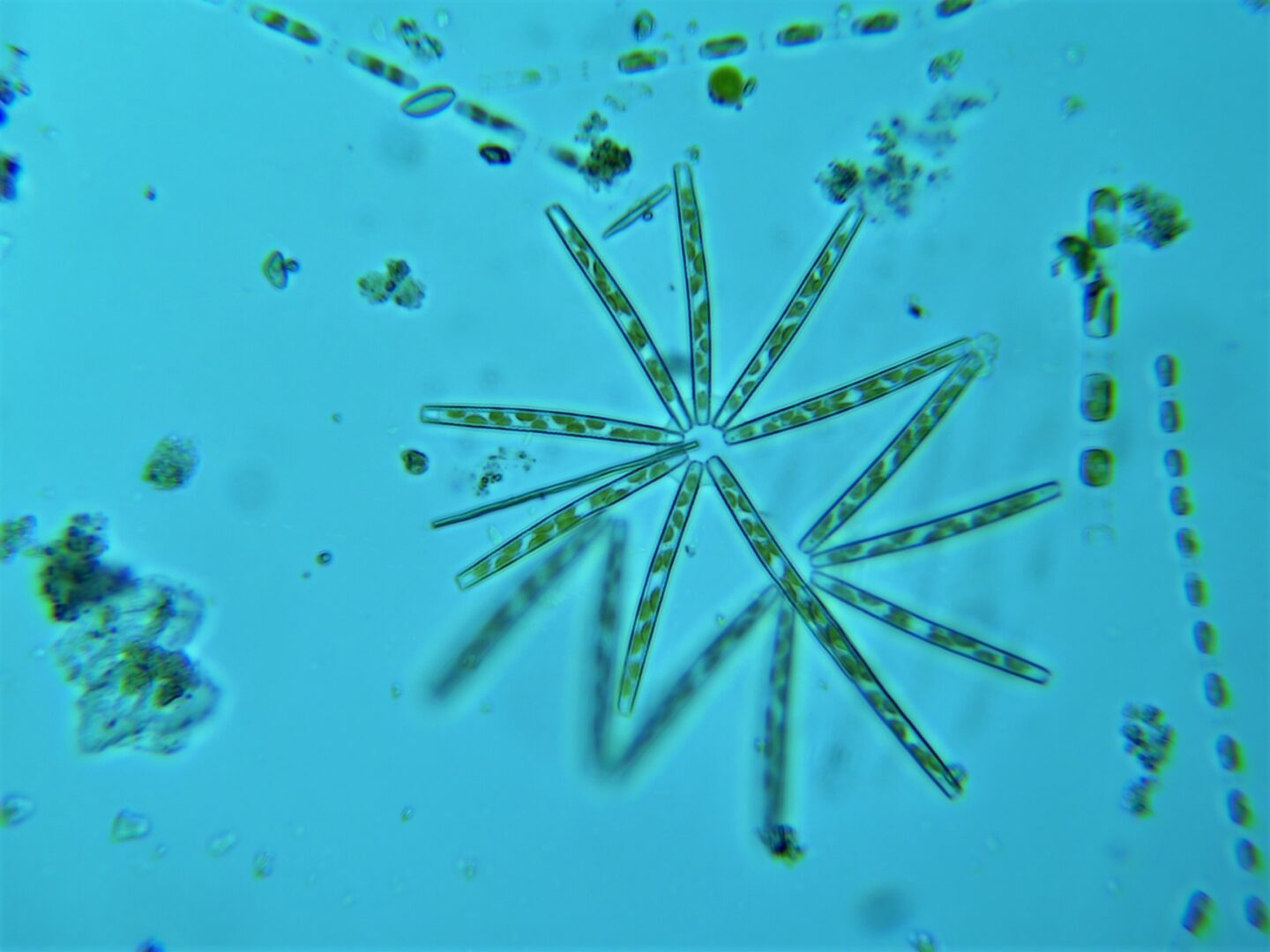

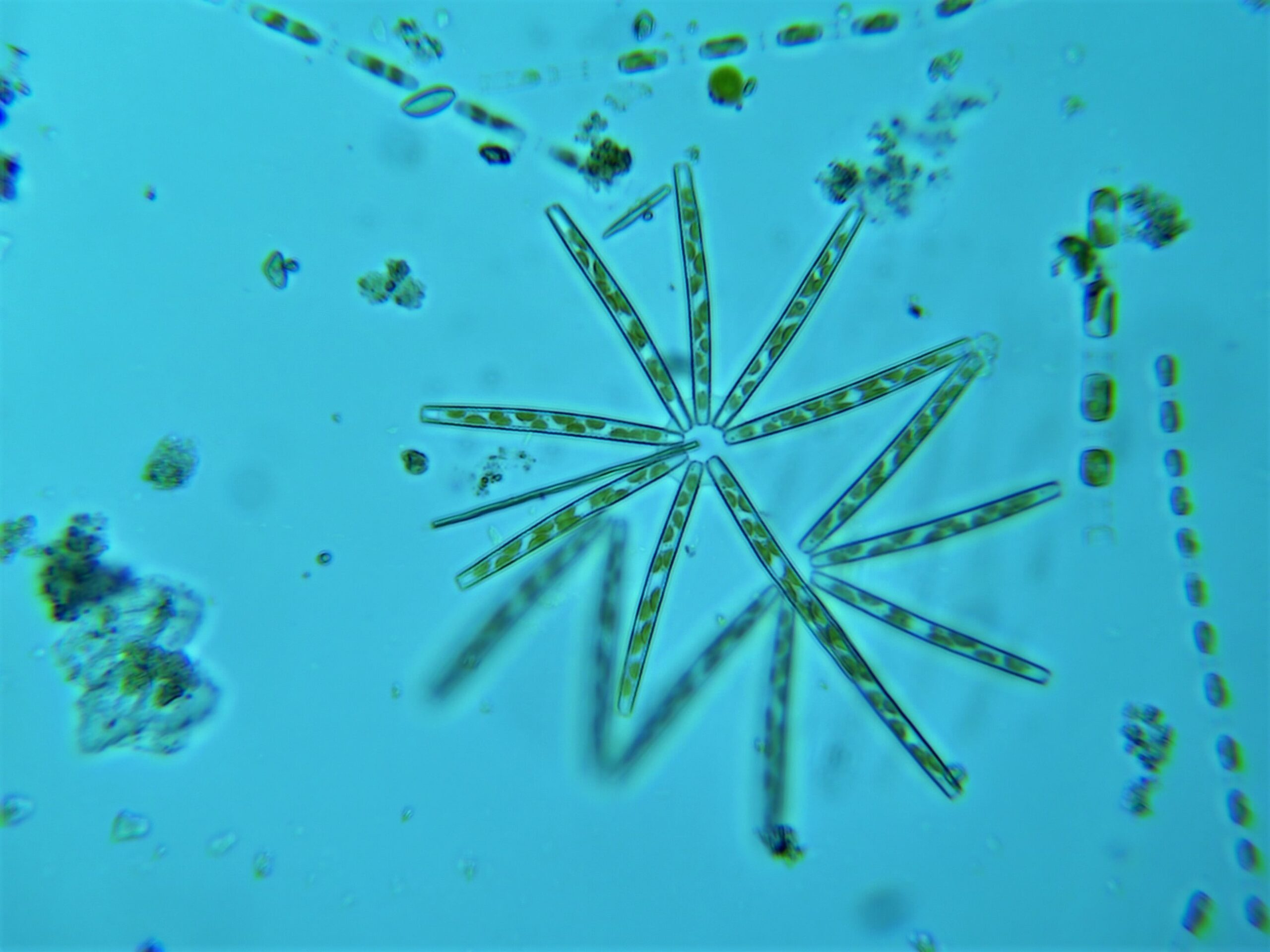

Phytoplankton are a critical part of marine food webs because they provide resources that many other organisms need to survive, including humans, because phytoplankton produce 50% of oxygen worldwide! Our River Project team commonly observes phytoplankton in our River samples that include diatoms, single celled algae with cell walls made of silica; dinoflagellates, single celled organisms that have two distinct flagella and feature characteristics of animals and plants; and cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae, a group of bacteria that carry out photosynthesis to produce food.

Shortly after the phytoplankton bloom begins, we observe increasing populations of other kinds of plankton that rely on phytoplankton for food, including zooplankton or animal plankton. You can usually identify a zooplankton by looking at their bodies, and seeing if they have features we normally see in animals, such as eyes, legs, hair or other body parts. While most zooplankton are very small, there are some exceptions. The lion’s mane jellyfish, for example, can grow to over six feet long, but is still a zooplankton by definition because it cannot swim against the movements of the water. Some zooplankton, like copepods, will remain plankton their entire lives, while others, such as the larvae of fish, crabs and shrimp, will grow into free swimming adults called nekton.

Shortly after the phytoplankton bloom begins, we observe increasing populations of other kinds of plankton that rely on phytoplankton for food, including zooplankton or animal plankton. You can usually identify a zooplankton by looking at their bodies, and seeing if they have features we normally see in animals, such as eyes, legs, hair or other body parts. While most zooplankton are very small, there are some exceptions. The lion’s mane jellyfish, for example, can grow to over six feet long, but is still a zooplankton by definition because it cannot swim against the movements of the water. Some zooplankton, like copepods, will remain plankton their entire lives, while others, such as the larvae of fish, crabs and shrimp, will grow into free swimming adults called nekton.

While phytoplankton act as primary producers, zooplankton take on the important role of primary consumers! By eating phytoplankton and sometimes smaller zooplankton, zooplankton help to move nutrients and energy up the food chain, where they are available for other, larger organisms to consume. Without phytoplankton and zooplankton, we would have lots of hungry fish, shorebirds, whales and even people, especially in fishing communities that rely on healthy marine ecosystems. For this reason, it is important to study plankton populations, particularly in areas where these populations are being affected by pollution, climate change and other human activities.

Ready to learn more? Explore the photo gallery above to see what phytoplankton our River Project team has been observing under the microscope during this year’s plankton bloom! And check out this NY1 story where Tina Walsh, HRPK’s River Project’s Senior Director of Education and Outreach, discusses the annual plankton bloom and how our River Project team engages New Yorkers with the Hudson River. Teachers, your students can learn more about plankton with us this spring too during our virtual Plankton Microscopy program as well. To learn more you can also email [email protected].