How do we collect and process eDNA from our local waters?

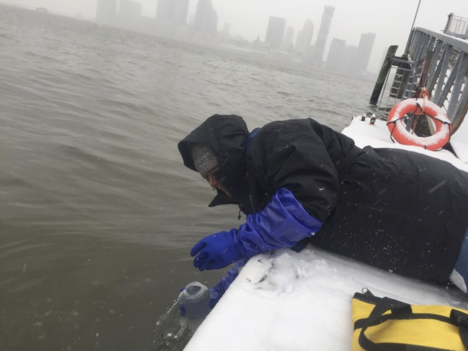

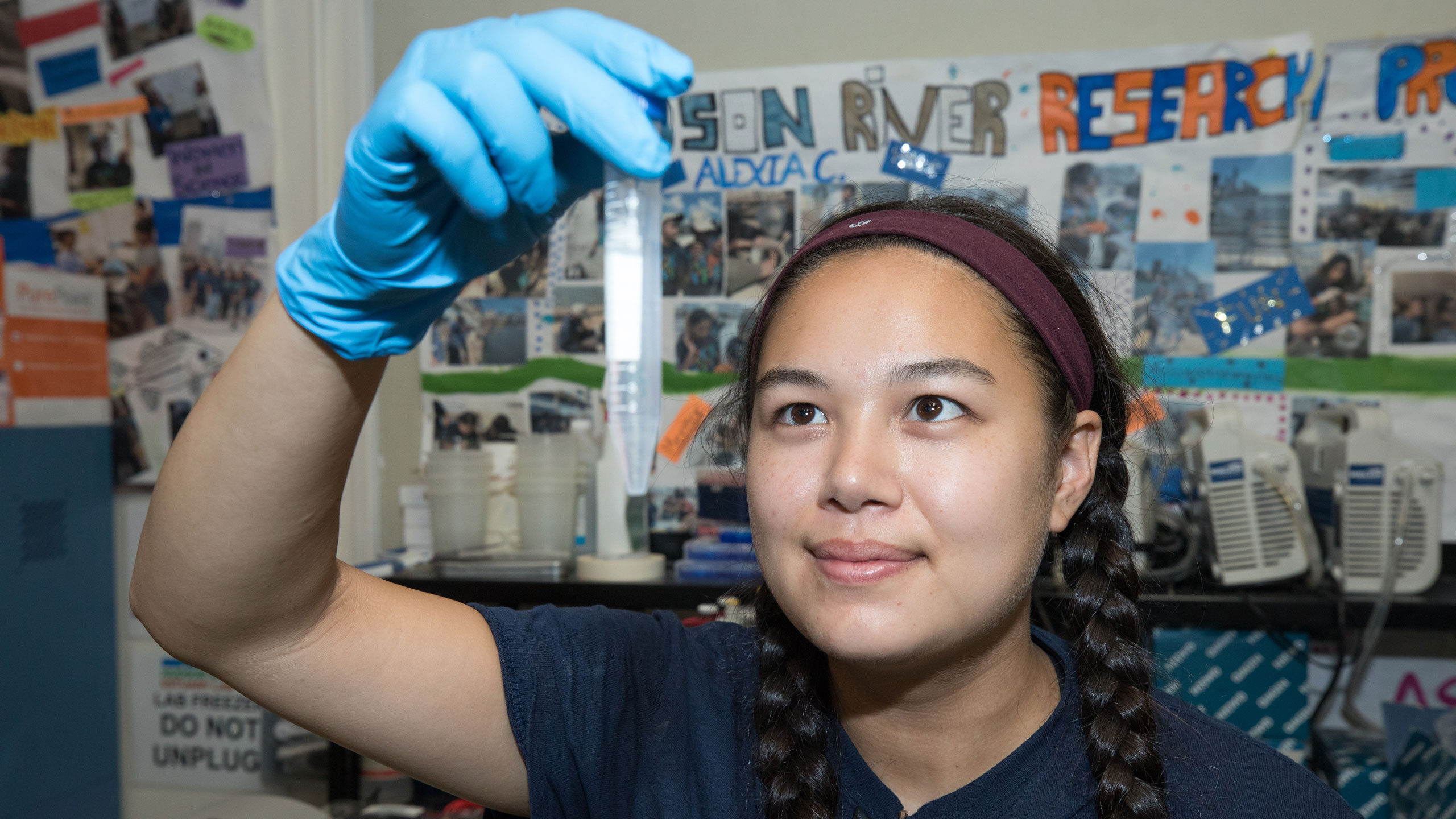

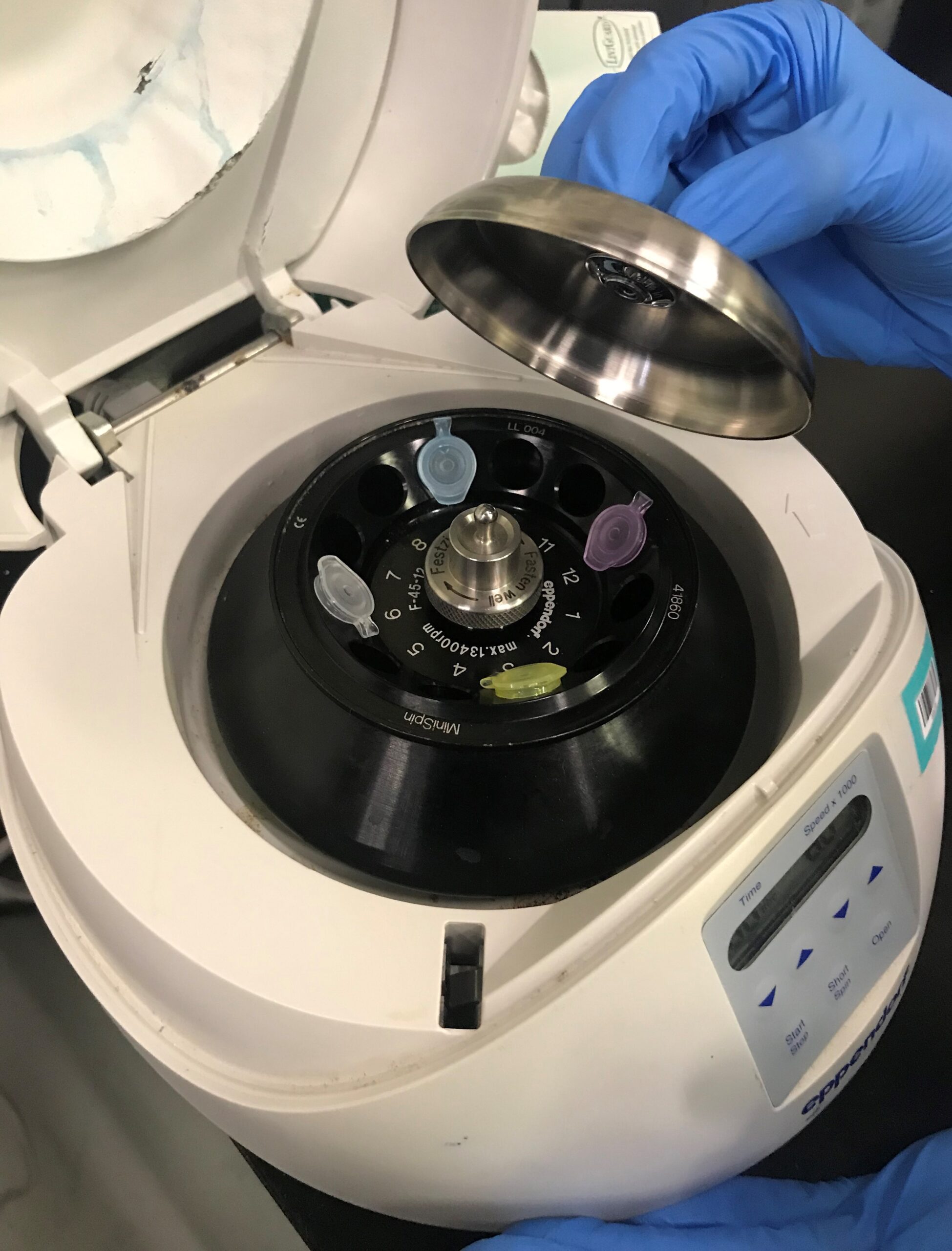

Park scientists study eDNA by regularly collecting one-liter water samples from the River at various locations. These water samples are filtered to collect the eDNA fragments on specialized nylon filters. The eDNA is then extracted from the filters through a series of steps that separates and concentrates the DNA from the rest of the sample. Once amplified, species are identified by sequencing short “barcode regions”, which are known DNA sequences that are unique between species, essentially functioning as genetic labels.

DNA has what is called a double helix structure, which looks like a twisted ladder. It has two phosphate-based backbones and “runged” nucleotides that pair together. Nucleotides attach in base pairs, with adenine (A) pairing with thymine (T) and guanine (G) with cytosine (C). The long sequence formed by these four base pairs is an organism’s genetic code. Each species has its own unique DNA sequence, encoding instructions that define them. And because the barcode region varies between species, it can be used to identify or track them.

To sequence the barcode region, the DNA must first be amplified using a polymerase chain reaction, or PCR. PCR artificially executes a process that occurs inside a living cell to replicate DNA using an enzyme called Taq polymerase. By doubling the amount of DNA with each cycle, PCR can make many millions of copies of the targeted region starting from very small amounts, making it then possible to sequence the DNA.

The resulting amplicons (amplified DNA from PCR) can help identify unique species in the environment through Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) techniques or basic gel electrophoresis. The large data set is analyzed using a special bioinformatics program, which counts, sorts and matches sequences with DNA barcodes within its database. A list of species for each sample is then created, along with an estimate of how much DNA in each sample came from each species. Though the quantity of DNA is related to the amount of fish, it does not tell us how many of each fish species are present because the relationship is complicated. This is because of inherent variance in the inconsistency of shedding DNA between species and likely even individuals, as well as the extent to which DNA moves in our system and how quickly it then degrades.

Why do we sample eDNA?

eDNA lets scientists determine what species are present in a sample with a process that is faster, cheaper and less invasive than traditional survey methods. eDNA can also look at many different species simultaneously, capturing a more comprehensive snapshot of the community, and is free from some method-specific biases common to conventional tools. Taken together, this means that in complex ecosystems, eDNA can be an especially effective survey method.

Why use eDNA for fish?

Fish live underwater and often have large ranges and behaviors that protect them from predators, making them hard to survey. Take, for example, a species of fish that spends most of its time hiding under rocks. This fish could be very hard to detect with cages or nets, so it might go undetected with traditional sampling methods. eDNA is very sensitive, and can detect sparse DNA from less numerous or smaller species, without being overwhelmed by too much DNA from common or large species.

As we continue to apply these research methods in our Estuarine Sanctuary, we will gain additional knowledge about fish presence and diversity. We look forward to sharing future applications of eDNA as a research and educational tool for our community.

Visit here for an interactive map highlighting notable eDNA findings from our research. Stay tuned as we share additional data and reports on our findings.